Hi! In the new year, as promised, you’ll see more actual science discussions on this page. I have - I think, for the first time since I started writing here - a plan for the next four posts. The first will discuss nuclear power and its place in the world. The second will tell you a little about its most interesting future alternative - fusion power. Next up, we’ll discuss its history a little and where I predict it’ll head in the near future; and in the fourth, I’ll try to discuss a little about what we’re actually doing with it in terms of research work. I can’t wait to get to the fourth part, so that should be at least motivating. Let’s get to it!

Let’s start with a disclaimer: I am not a nuclear physicist, the closest I’ve come to nuclear power is a trip to Świerk and a few too many hours in Factorio. If this post disagrees with nuclear physicists, you should most likely trust them over me. This is not meant to be reference material in any way; it’s a knowledge dump of where I’m coming from, so you can understand where I’ll go to in later posts.

Also, I rarely write these, as I think this kind of message should be implicit in just about everything you read on the Internet; but I feel it’s worth the reminder here, and I thought saying this “out loud” might stop me from procrastinating on writing this. And now, without further ado…

I shall not bore you with the details of nuclear fission’s use for power generations. Many have written on that before, and I don’t think I can add much to that. Basically, though, and in great simplification - take the following diagram of, essentially, how much energy, per atomic nucleus, you need to break up an atom:

notice that the most stable nuclei are at the “Fe peak” (which, coincidentally, you could also call the “iron hill”, and which, also coincidentally, is where most matter in the universe might reach steady state, and in other words, where time would seem to stand still, which sure puts a new, er, spin on that song). Once you’ve noticed that, you realize that if you can find some way to split heavy elements into light elements, you would probably release that energy (going by the plot alone, about 1MeV from U238 to stable Fe56) and could harness it. Hit some particularly heavy nuclei with enough neutrons…

and you’ve got nuclear power, in a nutshell! Simple, right? Simple to the point of throwing out the actual science. I completely neglected a lot of factors: the fact that you want the neutrons to hit the nuclei slowly enough not to cause a runaway chain reaction chief among them. But this is meant to be a simple view, and that neglect is a tragedy we’ll have to live with. Anyway! We all know the pros and cons for nuclear, but, to recap:

- No carbon emissions

- High energy density of fuel means logistics become easier

- Stable base load capability

- Risk of proliferation of fissile materials

- Nuclear waste needs to be stored

That last point is, actually, usually blown out of proportion. Something I’ve learned about recently is that all nuclear waste, since the origin of nuclear power until today, stored comfortably, safely and up to proper regulations, would fill a football field. Does that sound like a lot? Does it, still, when I tell you that our Polish Bełchatów coal power plant’s coal ash storage area takes up 416 ha (which translates to ~590 football fields), and that was already 60% filled up by the 2000?

Yeah, didn’t think so.

Base load

But I’d like to focus on the base load, here, and say a little more about that. Base load power is power that must be generated constantly, that is needed by e.g. refrigerators, hospitals, water processing plants, monitoring - processes that cannot really be turned on and off.

Base load is sort of the antithesis of most renewable energy sources. The most popular are wind and solar, and the conditions attached to them are in the name. They’re variable power sources, and while I think they’re absolutely great, their variability makes them ill-suited to fill out our entire power demand.

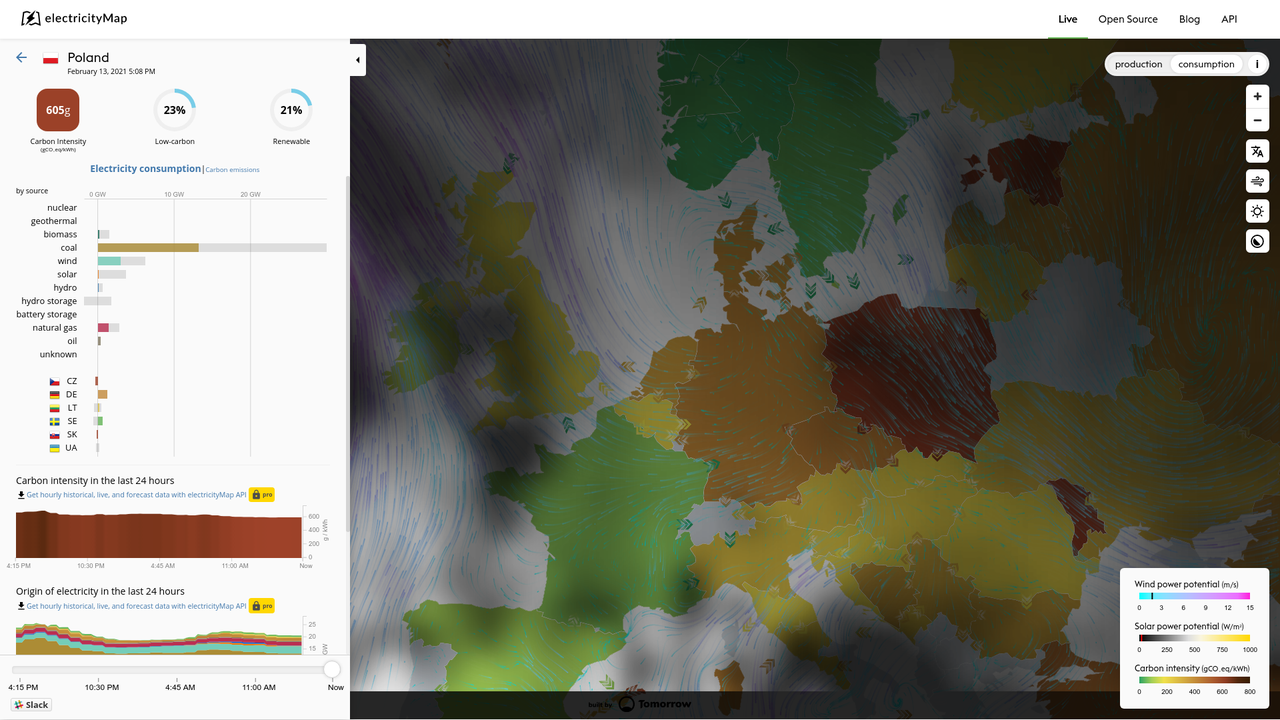

Let’s take a look at an example. Let’s go to electricitymap.org and check a few European countries. Note that we’ll be, technically, looking at power consumption, rather than production; but it doesn’t make that much of a difference. As I’m writing this, it’s 17:20 CET, a cold and cloudy Saturday. How’s my home country of Poland doing?

Poland

Well… badly, as usual. We’re taking some baby steps in transitioning away from coal as our main power source, and our government hasn’t really been all that helpful with promoting the growth of solar or inland wind power. There is talk of adding 6 GW of nuclear power in the next decade(s), but not much to brag about right now.

This is, basically, the darkest scenario of “fossil fuels for base load, little renewable energy”.

Germany

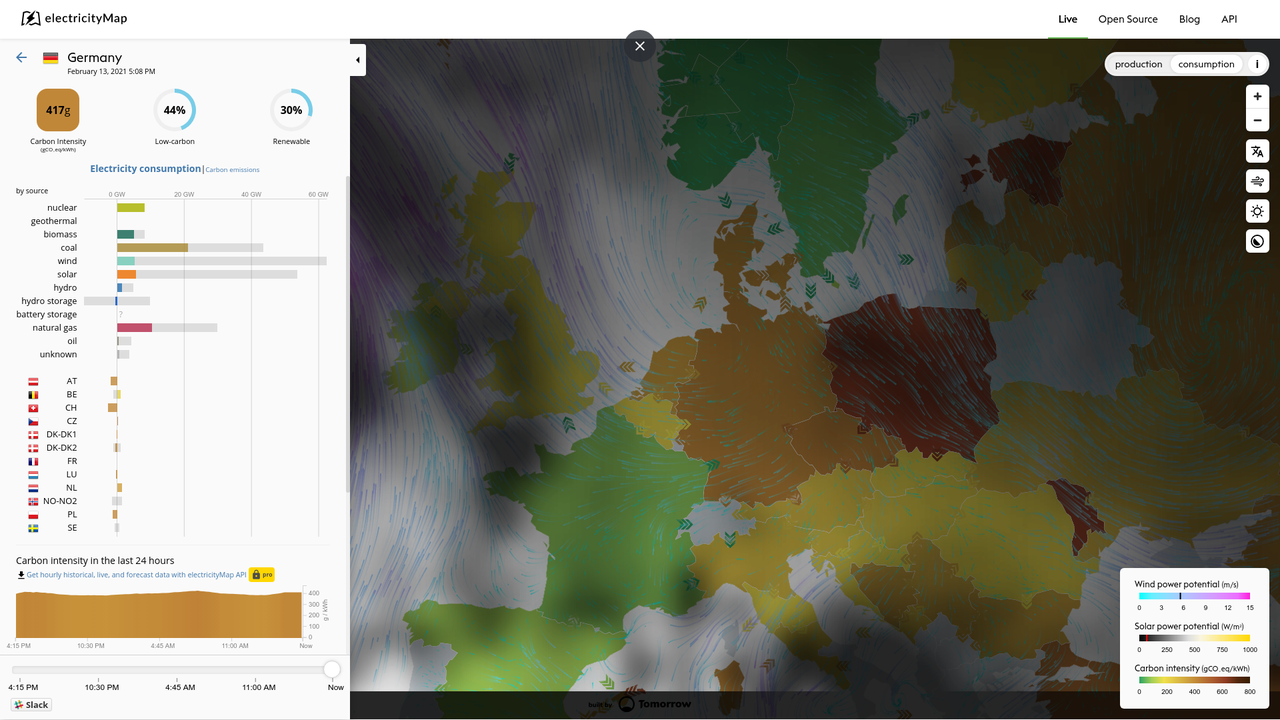

Let’s go to our western neighbor, Germany. Germany, under the leadership of CDU with major Green influences, has been a big proponent of renewable energy. That’s certainly a fine idea, but let’s see how it’s going for them:

Well, they sure have a lot of capacity (maximum power they could, given optimal conditions, generate) for solar and wind! It’s a truly awesome (as in, I’m awed right now) set up - they have more wind power capacity than the entire power capacity of Poland, from what I can see.

But as you can see, it’s a cloudy winter day and it’s not all that windy. So, all that capacity gives them squat Thus, coal and gas usage both spike up, which is less than ideal when you’re trying to limit the amount of CO2 that goes up into the atmosphere.

Note that Germany did have a sizable amount of nuclear power generated, but, under the same CDU/Green leadership, closed them down. I don’t want to go into debate on the arguments made by both sides, whether those were made in good faith or not, whether they took all relevant factors into account or not; but, purely from a “let’s stop climate change” perspective, doesn’t look like it’s been a good call for them.

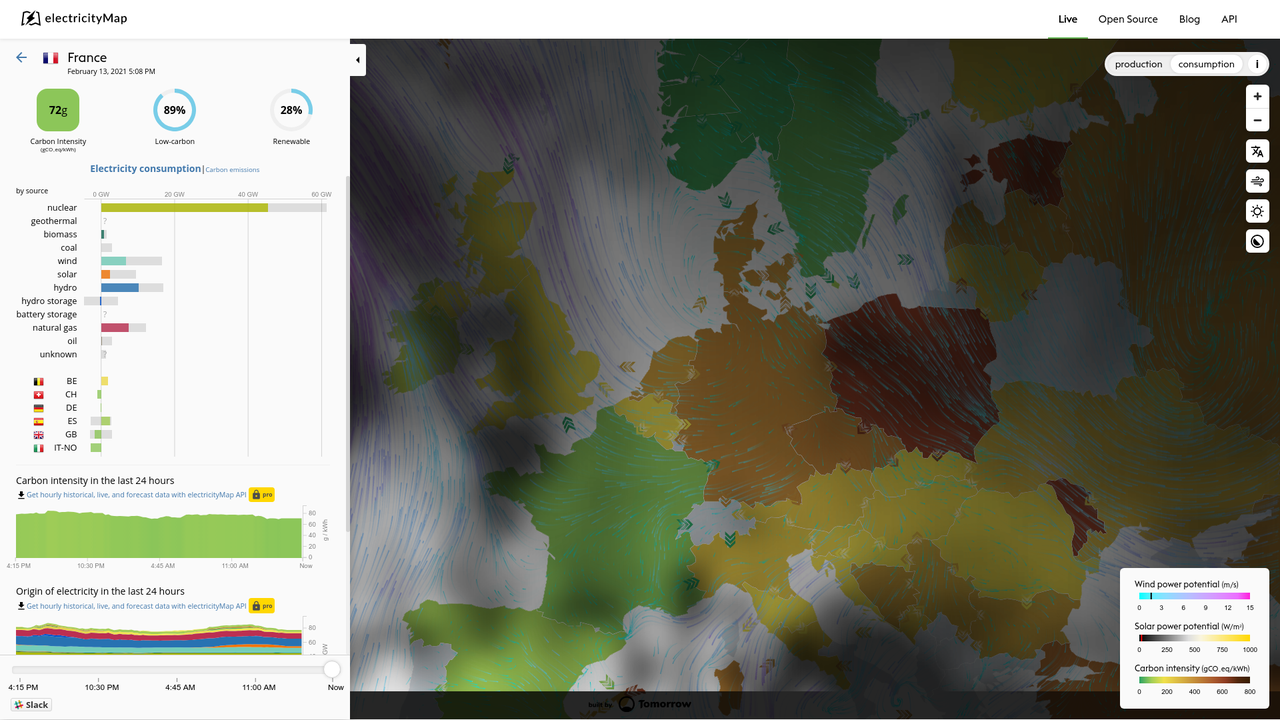

In contrast, let’s go further west:

France

And this is the best example I know of what happens, in two similar countries, if one decides to close their nuclear and one does not. Notice how they still burn some natural gas. “Natural gas” is a nice name for what is still a fossil fuel, still emits CO2, less so than coal, but still - but even with that, you emit a way less CO2 than Germany.

Takeaways from a winter day

- Renewables are awesome, but they don’t work under all conditions. You need that base load power, for sub-optimal conditions which pure renewables don’t cover; and the less carbon intensive that base load you can make, the better for you and for the world.

- There is a clear need for non-CO2-emitting power sources that can produce base load power.

- People are closing nuclear power plants and it seems that they’re wrong to do so. If it were up to me, I would declare an instant moratorium on any action that harms the continued operation and each and every nuclear power plant - if they’re already up, keep them up and don’t touch them. Each of them is a vital weapon against climate change.

There is, of course, renewables + storage; but I don’t want to make this post too long, so, in short: the technology really isn’t there just yet, nor does it scale enough. Eventually, given breakthroughs in material science - could be. But once again, it’s not going to be the alpha and omega of power generation; just an element of the energy mix.

So, this is where we are in 2021.

Next week, hopefully, I’ll be able to tell you - with fewer simplifications! - about an alternative scheme that accomplishes the same goals as current nuclear. Have a great time until then!